Recent Posts

The Multiverse Myth

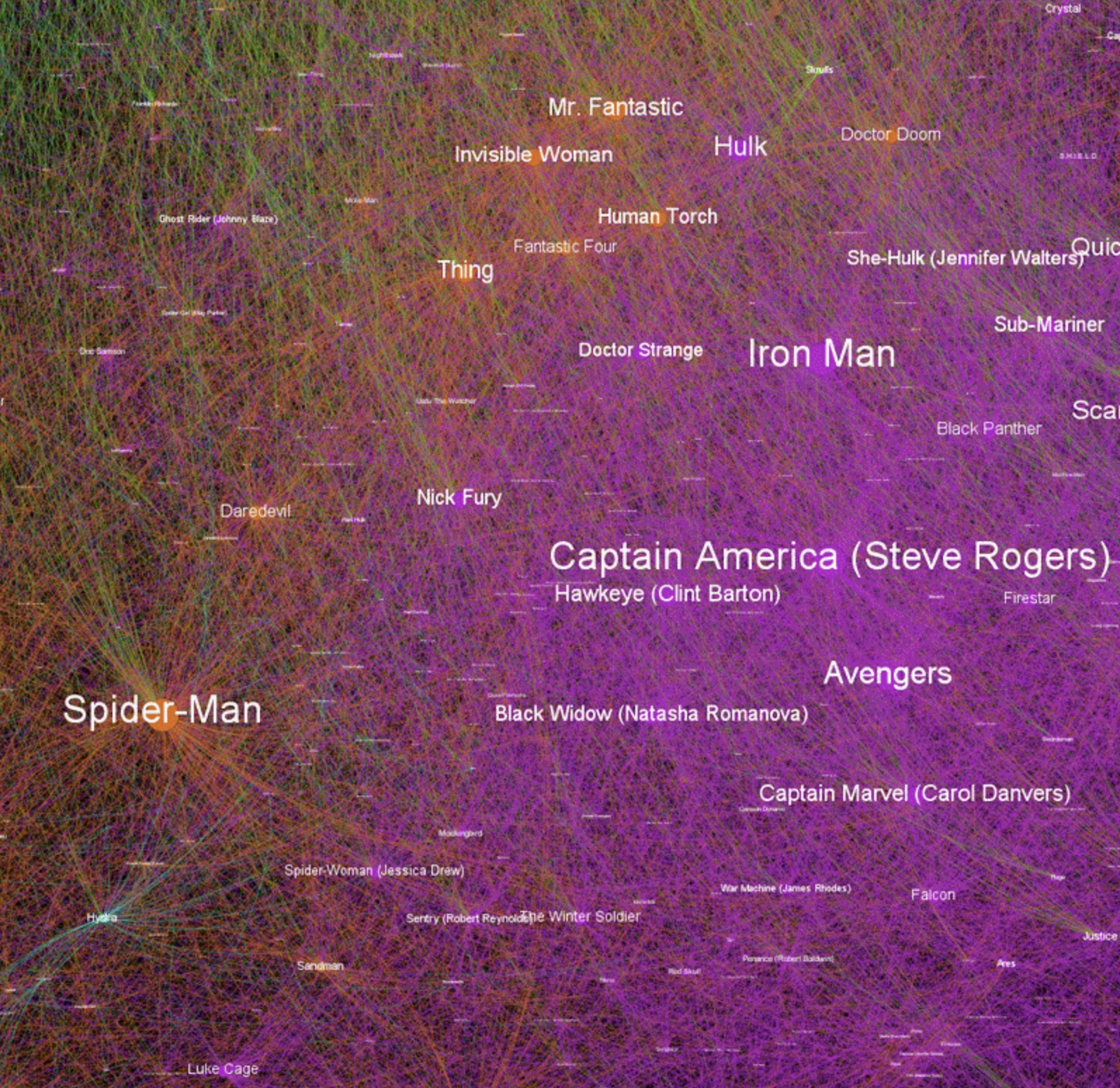

Over the last few years, I’ve heard different people in the entertainment industry say something along the lines of “because of Marvel, people get what a multiverse is.” This is always in the context of speaking about another brand with multiple worlds, storylines, and lots of characters, and they say it as though Marvel has cut through a Gordian knot for their tangled intellectual property.

Whenever I hear it, I know I’m talking with someone who misunderstands what the Marvel cinematic universe did, how they did it, and how it does or does not apply to other brands. Also, I suspect they don’t see that Marvel’s recent string of wobbly releases is partly because Marvel seems to be forgetting what it did and how it did it.

Multiverse = X

If you look up the definition of multiverse, it’s pretty loose. Even in the context of cosmological science, there’s varying interpretations of what the term encompasses. (Is it all possible universes? Only the observable universes? Does it mean infinite possibility, even extending to the uncredible?) For the purposes of entertainment brands, it’s any intellectual property with lots of characters, lots of storylines, lots of settings, lots of genres, lots of worlds, lots of universes, and/or multiple alternative timelines.

There. I hope that cleared things up.

I could tell you what I think multiverse should mean, but that won’t change the fact that the entertainment industry uses it in all sorts of ways. The problem created by that diversity of meaning and complexity is precisely why some folks in the entertainment industry want Marvel to have solved it for them. Marvel solving the problem means you can just lay out your messy, complex IP, and consumers will understand it. They’ll even like it! They like the Marvel cinematic universe, and therefor they like multiverses, right?

Cinematic Universe ≠ Multiverse

Dissecting the mechanisms of success behind Marvel’s cinematic universe and why recent releases fail to follow through on that strategy is the subject of multiple dissertations and whole books. For this essay, it’s only important to establish one fact: The multiverse ain’t it.

Nope. Marvel found success with its cinematic universe because it followed the tried-and-true strategy of making a good story about a single character, and then building the next great story. Remember, Marvel’s cinematic universe started with Iron Man, not with Guardians of the Galaxy, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, or The Marvels.

Also, it’s important to note that this wasn’t Marvel’s first bite at the apple. There were plenty of Marvel movies before Iron Man started the process of creating the Cinematic Universe.

I’d argue that some of Marvel’s recent stumbles are in part because it’s been relying too much on audiences understanding its interconnected stories. Yes, a teenager sitting down to watch the next Marvel movie or TV show can go back and watch everything, but Iron Man might be a movie that came out before that teenager was born. Easter eggs for the super fans are fine, but if a consumer must grasp the totality of the cinematic universe to have a compelling experience, that’s a mistake.

But that’s just the cinematic universe! The multiverse is a concept within Marvel’s cinematic universe that there are multiple timelines and therefore many alternate universes. Marvel’s Cinematic universe has used this concept only in a few places, with varying degrees of success. Most of Marvel’s multiverse lives in its various comic-book incarnations.

So, if Marvel has trouble storytelling with its multiverse and is struggling to navigate its cinematic universe, why on Earth would Marvel’s multiverse be the silver bullet for a wildly different brand with a different fanbase?

Making Your Multiverse Work

If it’s a new intellectual property, the problem created by the “Marvel solved it” thinking quickly sorts itself out.

“Hey consumer, I’ve got a new IP for you with multiple characters in different storylines on different worlds—and even different timelines—only held together by the thin veneer of being in the same multiverse under a single brand name!”

Sorry, friend. You’ll be lucky if your new brand survives six months. And RIP to your marketing department. Let me know where to send the flowers.

Most brands that have a multiverse have been around for more than a decade. They probably got a multiverse by accident; it was something that accreted onto the brand as successive generations of creators and company leadership came and went.

Brands like this can have wildly divergent fanbases for different parts of their IP.

A lot of brands that have multiverses got their start in the sixties or seventies. They’re now about half a century old. The brand might be twice or three times as old as people in its target market—all while still having fans who are a decade or two older than it. Some small fraction of that consumer base (largely its eldest members) are fans of its multiverse. They stuck by the brand through all its shifts and weird additions. But a lot of the long-term fans fell in love with some sliver of the brand. Their entry window was one character or one story, probably set in just one world and one timeline. Through it they might have become a fan of a larger slice of the multiverse pie. But the vast majority of the gnarly history of the brand (fifty years of content!) is completely foreign to them. Your younger consumers—the crucial next generation of fans—might be wholly new to the intellectual property besides basic brand identity and being able to identify a few of its most famous characters.

What happens when you give this diverse group of consumers the whole multiverse?

That’s a mistake, but it will probably take a few years to learn the lesson. Initially, the “Marvel solved it, here’s the multiverse” strategy will seem to be working. You’ll hook a lot of those long-term fans, and they’ll create buzz that gets new consumers curious. But you’ve fundamentally broken the mechanism that sustains the brand for the long term.

People don’t fall in love with multiverses. They fall in love with characters in compelling stories that they can comprehend. They become fans of the multiverse in the way people always have: a compelling experience with one character and one story that expands, and then another compelling story gets told in the same world, and so on.

If you’re not attempting to grab people on that human level—if all you’re selling is the multiverse—you’ll eventually scatter your fanbase to the winds. The multiverse-first strategy gives people a whiff of what they want, but it leaves them hungry. Eventually, they’ll go look for a meal elsewhere.

I mean, I get it. Attempting to continually hook fans with something new seems scary and hard. What’s compelling to a 70-year-old and a 7-year-old are usually very different, so what do you make for your decades-old brand? Plus, you’re sitting on decades of content. Why take risks? Why not just throw open the doors to that vast media cabinet and let them consume whatever they like from the nose of your most recent releases to the tip of the long tail? Give them the multiverse, right? Marvel has made it easy, right?

No. But don’t give up on your multiverse!

Most brands that have one have had it for years. And it’s no use trying to get rid of it. Retconning your multiverse away is a decision later creators will inevitably undo, effectively adding another layer of complexity to your multiverse.

The key to continued growth and maintaining the fanbase for a brand with a multiverse is leaning into the characters and their stories and into the distinctions between the brand’s disparate parts. If your brand has different worlds, alternate timelines, or sub-brands for different groups, you must figure out the characters and stories that are the audiences’ windows into them.

Try to make people fans of some thing, not everything.

Then, as you’re doing that, keep the multiverse in mind: If characters are windows, then the multiverse is a building with all those windows.

If you want your multiversal stories to combine into something like the Marvel Cinematic Universe, the rooms we see through those windows need to feel like they’re in the same building. The life and story of your individual characters should be unique and fascinating, but if you zoom out, it should be clear that we’re looking at a building that represents a home, or an office, or a museum—some greater place that has an overarching theme.

That’s the key difference between the DC and Marvel strategy for movies. Marvel had a chief architect trying to keep the whole structure in mind. DC didn’t.

Even something as gnarly and complex as a multiverse can set a tone and have a theme. Star Wars and Star Trek are very different brands. Both have extremely gnarly multiverses: in Star Trek’s case, there are literally alternate universes and timelines; Star Wars has various retcons and storylines that operated independently for years before the recent spate of films and TV shows ditched its Expanded Universe and chucked a bunch of the canon. But fundamentally, Star Trek is about exploration and empathy, whereas Star Wars is about conflict and morality. (It’s in their names!) Star Trek can do war stories. Star Wars can explore new cultures. But when either brand has a story that diverges too far from its core theme, it loses its way.

So, zoom way out to look at your multiverse and try to come to grips with the message it’s sending. Then zoom way back in to the life and story of one character and build the compelling experience from there.

Heads Up, General!

If you’re one of the creators in the trenches, all this advice might not mean much for your work. There are generals at the executive level who are giving the orders. You might have a general whose decisions seem tactical rather than strategic. They’ve seemed focused on quarterly results rather than long-term plans that would benefit the brand or company for a decade. Well, the truth is that most folks in leadership don’t have an incentive to look beyond the next quarter or the next rung in the corporate ladder, which is oftentimes at another company.

If you can, help your general to look not to Marvel’s multiverse as a solution but to Disney as a whole.

Disney bought Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion on 2009 and Lucasfilm for $4 billion in 2012. The company did not make those investments to boost just the next quarter’s profits. Those were huge bets designed to pay off for years to come. Recent data suggests they’ve made Disney about $12 billion, each. I’d critique some of the creative choices of those brands, but there’s no denying that Disney is looking for long-term sustainability with both. And that long-tern view is paying dividends—quite literally.

If your brand already has a multiverse, then you don’t need to invest $4 billion dollars, but you do need to invest thought, time, and yes, money in developing your strategy for long-term health. Those costs are an investment in your future. It’s not a strategy without risk. Yet, Disney didn’t know when their bets would pay off, but do you think Disney regrets taking the chance?

Throwing open the doors to the multiverse without a plan can result in a quarterly boost (or several) , but if you focus on the human level of compelling characters in quality stories, it opens the door to greater profits over time.

But What About Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse?

That’s a movie that plunged the audience into a new-to-them multiverse, and its plot hinged on the audience understanding and liking the concept. So, what about that?

Well, you got me there. All I can say is this: If you can make your brand new multiverse concept as compelling as Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, I think you’ll find success.

But What About Fortnite?

I’ve also heard Fortnite held up as an example of the popularity of multiverses. I struggle to express just how wrongheaded that is, but I’ll give it a shot.

Fortnite is a very popular game that was hugely popular before it allowed players to play in skins from their favorite IPs. Yes, there is a narrative that ties together characters from Stranger Things, Bad Boys, Ghostbusters, and the X-Men. And yes, it hinges on the idea of a multiverse. But the whole point of putting all those IPs into the game is that players can express their fandom of outside IPs to other players, not engage with the Fortnite IP. Its multiverse is a fig leaf covering the naked commercial reasons to change its gameplay and introduce already-popular characters from other IPs.

And it only works because Fortnite itself is popular. Put all those IPs into a less successful game with a similar veneer of story, and you might sink it under the burden of those licensing agreements rather than buoy its profits.

Funko used a multiverse story for its Funkoverse game. The concept of a multiverse was so key to its concept that the game’s name smashed the company’s name and multiverse together. I worked on it. It was a good game. The whole point was the giddy fun you could get from having Harry Potter face off against Thanos or the shark from Jaws. Yet even with all of Funko’s marketing muscle behind its multiverse, not enough consumers wanted to play battles between the Batman and Robin and the Golden Girls. There are all kinds of reasons why comparing Fortnite to Funkoverse isn’t apples to apples, but my point is that Funkoverse had a multiverse—one made up of hugely popular characters from all over pop culture—and it did not thrive.

The mere existence of a multiverse in your IP is not a panacea, and it is not a marketing asset. Consumers can comprehend the concept of a multiverse, but it doesn’t mean they want it. Don’t let Fortnite’s or Marvel’s successes make you believe in the mythical popularity of multiverses.

Don’t Tolkien It

When you design an IP, you do not need to invent whole new languages or a ten-thousand-year history. I have tremendous respect for J. R. R. Tolkien’s creations and his contribution to culture, but following in his footsteps leads to folly. He wrote various bits of fantasy for his children, and he invented languages because he was a linguist. He wrote the timeline to explain the creation of his languages. Only then did he write The Hobbit, but it was without intention of publication. It was only when passed among friends that it fell into the hands of a publisher. The success of his works is due to their quality, yes, but it is also a sheer accident of history. The creation of languages and a detailed timeline were part of Tolkien’s writing process, but unless that’s a natural part of your process, you’ll be wasting a lot of time and energy.

Don’t Create Detailed Timelines

Pop quiz!

- Woodstock

- Cuban Missile Crisis

- MLK Assassination

- JFK Assassination

- Moon Landing

- Civil Rights Act

Maybe you do better, but I flunk this quiz.

Not knowing these things isn’t a personal failure nor does it reveal flaws in your education. It’s human nature. Most people have only a vague understanding of history—even our family histories. We can recall key events and important people, but it takes a lot of effort to keep them ordered properly.

As human beings, we have always relied on touchstones to navigate our understanding of history. We collect those events and people and categorize them in mental buckets (American history, WWII stuff, ancient history, and so on?), and we can usually put those buckets on a timeline in the right order. But the farther events are from our own lives, the less likely we are to know about them, to know exactly when they happened, and to know why they were important.

This is even more true for fictional worlds.

People in a pre- or post-literate society will have even less of a grasp of their history than you have of your own. Most characters in a fantasy or post-apocalyptic setting will lack access to knowledge of history other than through word-of-mouth storytelling. In a futuristic setting, people will likely rely more heavily on technological resources for understanding history. Think about Star Wars or Star Trek with their countless worlds and varied peoples and societies. No one would expect to keep it all straight in their heads, and they’d rely on digital libraries or artificially intelligent computers to tell them what happened in the past.

Now think about the consumers of your fictional worlds. They only know as much as you tell them, and even if you give them a detailed timeline, they’ll likely only remember a few touchstone events without going back to it for reference.

Finally, think about the other creators who might contribute to your worldbuilding. It benefits them to have a few important touchstones to wrap their heads around, but a detailed timeline obfuscates what’s important, and it ties their hands when they want to add their own inventions.

So, what does this mean for worldbuilding?

It means that detailed, ten-thousand-year timeline is a lot of wasted effort that likely hurts people’s ability to comprehend your setting. Also, a single detailed timeline still doesn’t get you any closer to verisimilitude because people from different places have their own histories. Important events don’t all happen in one place. If your setting has more than one society, then each would have its detailed history.

Maybe you’re a history buff and love the deep lore of worlds, so the idea of creating detailed timelines for several societies has you chomping at the bit. Resist the urge. You might enjoy doing it, and there are some others who might dig it, but for most people, it will get in the way.

To create a comprehensible and consistent IP, you don’t need a detailed history of each empire and its rulers and so on. You just need to know your touchstones and have them in rough order. The touchstones are the big events and important places that lots of people in the story would know a little something about, and they’re some of the things that would shape culture and create the visual elements of your setting.

So where do you start? Wherever you like! Throw some darts at the wall and organize them later. What you’re looking for are ideas in line with the thematic and tonal elements of your setting.

In fantasy settings, creators often start at the literal beginning, positing a mythic creation of the world by deific figures. You can go that route, but assuming the world has progressed a long time from that moment, then it’s just a myth to most people. Even if the deities that created the world are still walking around in it, the idea that they made the planet would be a story that people might or might not believe. If there are many cultures with different religious beliefs, they probably have different creation stories.

So, you can ignore the beginning of the world. You might instead start with the world you want to see in the present day of the story. Think about the characters on which you’re going to focus and in terms of the last two generations. The events in their lifetime and the lifetimes of their parents and grandparents have the greatest impact on their lives. The farther away events are from your main characters in distance or time, the less you need to know about them.

But maybe you don’t have your story and characters worked out yet. What then?

Make up some cool stuff, but don’t sweat the details.

For example: During an economic downturn, workers in some important country (or several??) had some color or flag they rallied around. The protests grew into a populist proletariat revolution.

Nifty idea. Lots of historical parallels. There was probably some leader or figurehead for this movement, but was this person more like Hitler or Gandhi? Did that person literally lead the charge or were they a symbol of the movement? What was the actual symbol of the movement? What was its flag? What colors did they wear?

Don’t sweat the details—unless it just happened.

The further back in time you set this event, the less the details matter. If it was a few years ago, the people involved are still alive, the colors they wore might still be associated with rebellion, and the consequences of their actions are felt daily. But if it happened a couple generations ago, time mollifies the event’s impact. If it was a thousand years ago, people remember very little besides broad outlines and oft-repeated anecdotes.

Consider the fasces. The fasces (an axe in a bundle of sticks) is the root of the word “fascism.” The Romans took the symbol from the even more ancient Etruscans and used it as an emblem that implied (variously?) royal prestige, coercive power, or magisterial judgement. Benito Mussolini’s fascist party of Italy—where we get the common usage of the word—used the fasces in its symbology. Yet today, the fasces gets used all over the place in decoration to imply a connection to Rome and the idea of power generally, much like we see white, fluted columns being used on everything from people’s homes to the White House.

Now consider the swastika. Its long history of usage among different cultures has been overshadowed by its use by the Nazis. If you’re looking for a symbol that says “fascism” today, this is it. Will the symbol be so freighted with meaning in fifteen hundred years? I’d like to think that the horrors of the Holocaust won’t be forgotten even then, but in all likelihood, there will be something even more horrible to overshadow it. Or maybe our modern age will crumble due to a solar flare or climate change, leading to a Dark Age where we lose our grasp on the past.

Even titanic events get blunted by the passage of time. You might think that proof of the afterlife or an alien invasion might leave an indelible mark on societies worldwide, and they would. Just not the way you’d think.

Consider what happened with the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan. These were horrific events that led to mass devastation and contributed to the end of WWII, and so were hugely impactful. But today, nuclear reactors power homes in Japan, which has one of the most vibrant societies in the world. The passage of time hasn’t fundamentally changed how we view those attacks on Japan (the USA has still not officially apologized, a fact that I find mind-boggling?), but so many other things have changed. The knock-on effects of the bombings are complex. Godzilla was written as a response, and now kaiju and giant mecha are a fixture of pop culture. I would not have had that on my bingo card. So, if you intend to set some dramatic event in the distant past of your setting, the way it affects the future should surprise you.

The passage of time also has a way of spacing out the touchstones with which we connect. Generally speaking, the farther back in time that you think about, the farther apart the important events become. The Fall of Rome was in 476 AD. That’s nearly three thousand years after the pyramids of Egypt were built. (Hey, bonus points for the quiz: That’s something significant that happened more than four thousand years ago, and people are still building pyramid-shaped things and learning about the ancient Egyptians.)

To sum up:

- Don’t write a massive timeline.

- Create the touchstones and leave the minutia for later invention.

- Place fewer touchstones father apart the further in the past you go.

- Lavish the most attention on touchstones nearest the present day of your story.

- Provide other creators with the touchstones and the freedom to create more.

- Keep a consistent timeline to keep your canon straight but remember that the audience only knows what you show them. (So don’t show them a timeline unless you want to tie your hands!)

Don’t Invent Whole Languages

As for inventing languages? Just don’t. If you’re not a linguist, it’s going to be terrible. If you are a linguist, it’s going to bore the pants off most people and fly right over their heads.

Examine that sentence: “bore the pants off most people” and “fly right over their heads.” Both phrases are metaphors rooted in common usage of English that would bewilder English speakers from a few hundred years ago and might bewilder non-native English speakers today. Languages are full of these metaphors and idioms that we take for granted. (Even “take for granted” is an expression that didn’t arise in common usage until the 1600s, at which time English sounded so different that a modern speaker would be forgiven for thinking it another language.?)

If you’re creating a fantastic or futuristic IP that uses English and not considering taking idioms and metaphors out or putting in new ones, why go to the bother creating a whole new language? I know, only a boring pedant would worry about using modern idiom in a story set a thousand years ago, a thousand years in the future, or on another planet. But if you’re making a whole new language and still using modern idiom, which then just gets translated into English so people can understand the story you’re telling, what have you accomplished? Why did you go to all that effort?

If the answer to those questions is some mix of verisimilitude and “because it’s cool,” fine. But treat it like a timeline: Make only as much as you need to create something comprehensible and consistent, and then leave as much room as possible for future invention.

But surely every alien or fantastic people can’t simply speak English! Okay… But are dragons or lizard people or skeletons or demons or aliens speaking a language even though they lack lips? Sure, only a boring pedant would take issue with that, just like only a boring pedant would worry about if they use modern idiom—or if they all speak the same language.

Yes, I know that there are people who learn to speak Klingon, and that is pretty cool. (Well, it’s assuredly super nerdy, but from the standpoint of the creator, it must be rewarding to have created a language and have people decide to use it.?) But is that really what you’re trying to accomplish, and wouldn’t your time and treasure be better spent elsewhere?

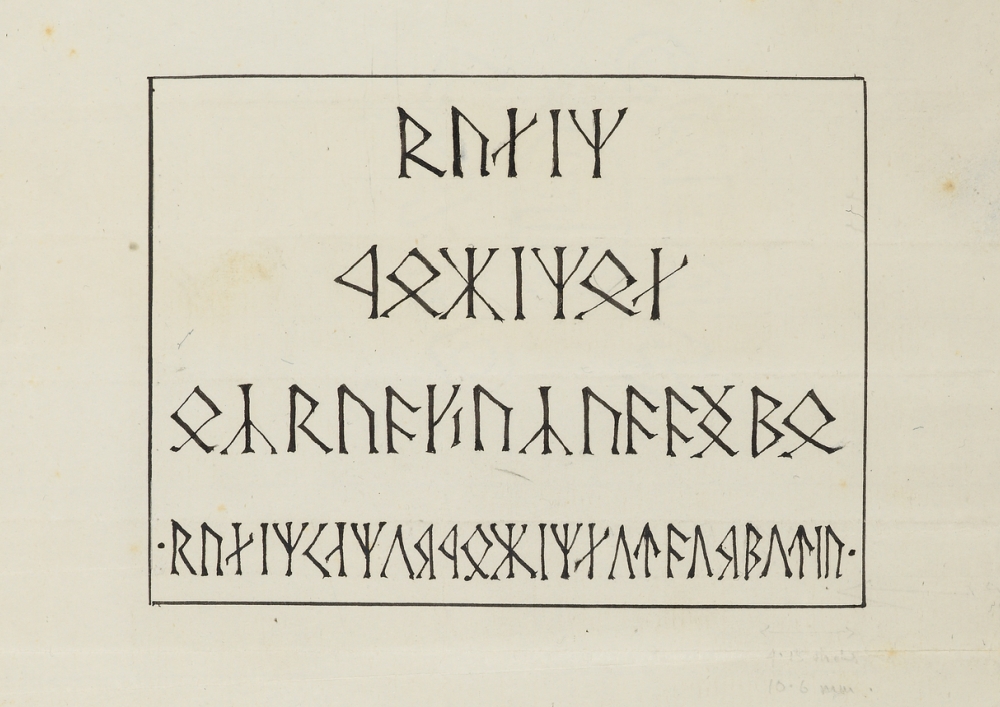

And what about fictional alphabets? Surely your invented language needs its own alphabet. That adds verisimilitude. Plus, they look so cool!

Again, think about how you spend your time and treasure. Most fictional alphabets end up being simple keystroke replacements rather than true representations of an alternative way of showing speech. And even once you’ve made that translatable alphabet, every time it gets used, you must decide if you write in English, your made-up language, or just lorem ipsum. Working with an artist to depict something? Well, be ready to check every image for a cheeky hidden message using your made-up alphabet.

Is your experience of the Star Wars franchise improved by not being able to read any of the signs or screens you see? They mostly speak English, so why are we seeing Aruebesh (which usually just translates to English with keystroke replacement?)?

The most compelling case that I can think of for an invented language is some kind of marketing stunt where there’s a secret message that super fans can puzzle out. Yet even in that case, you’re better off making it a unique puzzle that takes real effort to solve rather than a simple keystroke replacement.

But surely not all of the different aliens or fantastical species in the setting can just use English (or whichever is the native language of the audience?)!

Yes. You absolutely can do that. And most people won’t think twice about it.

Not There but Back Again

Now that I’ve said all that. Please understand that I have the deepest appreciation for complex, vibrant, and meticulous fictional worlds. I understand that exhaustive detail lavished on a setting can be a way for fans to fall in love with it. Yet, the ten-thousand-year timeline and invented languages are never the sparks that ignite the fires of fandom. Great stories with great characters do that. They’re the gateway to the beautifully detailed world you’ve created. That’s where you should follow Tolkien’s example.

Sanderson’s Hidden Law of Magic

If you are a creator of science fiction or fantasy in some capacity, you owe it to your craft to read Sanderson’s Laws of Magic. You can find his overview here, but to really understand them, you should read the article for each law.

I do them a disservice by doing so, but I’d sum up the first two laws in this way: Fictional science or magic only really works for your story when it functions within comprehensible limits.

But it’s magic! That’s the point!“

Listen, deus ex machina worked for the ancient Greeks, but audiences have moved on. Read Brandon Sanderson’s articles. He’ll do a much better job of convincing you than I.

The devious bit comes in with Sanderson’s third law: Expand what you already have before you add something new. I think Sanderson missed a trick.

There’s a hidden fourth law critical to developing magic or sci-fi in intellectual properties: Follow the unwritten rules.

The use of magic or sci-fi in a story often comes with defined limits. These are the rules that we see enforced during the story. Creators often look at such written rules and look beyond them for the “design space.” The general idea is that within the rules put forth, nothing says you can’t, which mean that’s a place for you to expand into. Sanderson encourages that, and I largely agree.

However, what creators—even the original authors of the rules—often miss is that the story created a subtext of unwritten rules. These unwritten rules can be hidden third rails, ready to shock you when you stray across them. My favorite examples of this are from Star Wars and Star Trek.

In the original Star Wars trilogy, we get both implicit and explicit rules about the Force. When Obi-Wan waves his hand at the stormtooper and says, “These are not the droids you’re looking for,” it’s prefaced by him waving his hand at the stormtrooper and looking in his face and saying “You don’t need to see his identification,” which the stormtrooper repeats back to Obi-Wan. As the scene plays out, we see that the stormtrooper is under Obi-Wan’s thrall and being mind-controlled in some way. When Luke later makes a remark about not understanding how they got past the stormtroopers, Obi-Wan says, “The Force can have a strong influence on the weak-minded.” In Return of the Jedi, we see Luke use the same technique on Jabba the Hutt’s majordomo, but then we see Jabba the Hutt upset at his underling for falling for the “Jedi mind trick” and Jabba himself immune to Luke’s mental powers. The explicit rule is that it works only on the weak minded. The implicit rules are about proximity, a hand gesture, and looking in the eyes. It’s a great example of adhering to the written and unwritten rules of the Force, and it's a great story moment as it immediately shows us how far Luke has come in his skill with the Force.

When Darth Vader first Force chokes someone in A New Hope, he makes a pinching motion with his hand at a person in the room and looks that person in the face. In Empire Strikes Back, he does the Force choke through a video transmission without making any hand gesture. Proximity is no longer an issue nor is the gesture necessary, but he still needs to see the target and have their attention. In Return of the Jedi, we even see Luke Force choke a couple of Jabba’s gamorrean guards, but he follows the rules: proximity, gesture, and eye contact.

The first three films reuse this in several ways, such as jedis moving nearby objects through space by proximity, gesture, and eye contact. In the Force-choking scene in Empire Strikes Back, Darth Vader breaks some of the unwritten rules (no gesture, vast distance), and that the escalation in Darth Vader’s power makes him more threatening.

But in movies and TV series released in later years, Darth Vader breaks the implicit rules earlier in the timeline. In Rogue One, he chokes someone with his back turned. In the Obi-Wan Kenobi series, he pulls someone out of window and has them float in the air before casually walking down the street and Force choking people to death at random as he passes. These escalations of his power critically take place before Star Wars: A New Hope. If he could do all these things before Star Wars: A New Hope, why didn’t he do them in that movie? Darth Vader even force chokes and floats the Emperor in Episode 1. If he could do that in all those earlier phases, why hold back against Luke or Obi-Wan in any of the original trilogy?

The answer of course is that the creators of those later stories (including George Lucas) were looking at the totality of what is possible with the Force in Star Wars and trying to one-up preceding depictions. They saw the “design space” to create an exciting new scene without taking into account the unwritten rules the narrative had already laid out. While such decisions might have seemed to have a good dramatic payoff, breaking the unwritten rules can throw people out of the moment and make them start critically examining the work.

Does it sink the IP? Not a behemoth like Star Wars. That’s like hand drilling a hole in the side of an aircraft carrier. But the thing is, it’s not the only hole. A lot of creative choices in the TV series and movies violate the explicit and implicit rules set up by the original trilogy. Sometimes a series or movie repairs some of the damage. Sometimes they make more holes. I trust the Star Wars IP will be with us for generations to come, but there will be plenty of people who see the patches in the hull or feel their feet getting wet and decide to jump ship.

Star Trek has a lot of similar issues, but the one I find most illuminating is how transporters work. Now, I’m sure that there’s some Star Trek tech manual that has been published or some comic book or novel that has gone deep into the weeds about exactly how transporter technology works, but that’s not what most people see. The implicit and explicit rules for transporters are given to you in the original series and largely adhered to in later movies and series.

How far can you transport?

Ship to ship, and ship to planet.

How many people/things can you transport?

As much as you can fit on a transporter pad.

What can you transport?

People and moveable things—the kind of stuff that fits on a transport pad.

Where can you transport?

To and from a transport pad, but often to or from a planet or from one ship to another without the person starting or ending up on a transport pad.

When can’t you transport?

Through ship shields, various sci-fi energy interference, and maybe a weird mineral or something.

These basic ideas come from the first series because the transporter was solving dramatic and production problems. They didn’t want to have to land a whole ship or a landing vehicle on every planet they visited. The small transporter pad fit in the studio. But these practical limitations of budget and special effects have a tremendous benefit: The small group being transported makes their interventions on other planets more like diplomatic missions than invasions. That fits with the optimistic themes that Gene Rodenberry wanted to present.

But nothing says you can’t transport from star system to star system or across a planet. Surely a transporter pad could be made that was powerful enough to do it.

Why not make transporter pads bigger? You could transport more goods and people. Why not a transporter pad as big as an aircraft carrier? You could transport whole ships.

Why not use a transporter as a weapon? Disassemble an enemy ship by disintegrating critical portions of it. Or you could transport bombs from a secret pad somewhere on a planet and proceed in a campaign of targeted killings.

But wait, what’s the pad for anyway? Why not use transporters to just send people and things all over the place from all over the place? Why even bother having spaceships?

This looks a lot like “design space.” This looks like we’ve found areas where a Star Trek story could be innovative, and where a creator could really leave their mark on the franchise.

They’d leave a mark alright, and it’d look like a hole in the hull of the IP.

You might not see an explicit reason why you can’t do these things in Star Trek, but there’s a host if implicit reasons why you shouldn’t. When you start breaking the technologies’ implicit rules, you’re actually breaking the IP’s implicit rules. Fundamentally, the Star Trek IP is optimistic: Star Trek stories are about a group of friends going on an adventure and finding they have common ground with even the most alien species. That’s reinforced in how transporters get used: small groups moving to and from alien worlds or ships. While technically you could write stories that mess with transporters, you wouldn’t be writing stories that feel like Star Trek anymore.

As the creator of an IP, you can make those implicit rules explicit to yourself and your team. Write down the unwritten rules, and then explain to other writers why they exist and why they’re not for public consumption. And then as time goes on, examine your IP for the other unwritten rules that might crop up. It’s a lot easier to maintain a consistent, compelling and coherent IP when you write those unwritten rules down.

A Prickly Problem

It happens on every creative project with a large team of collaborators. You can find them in AAA games or in any big-budget movie franchise. Someone has put a cactus in the pine forest…

I don’t mean a literal cactus in a pine forest. I’m using a metaphor that this essay will beat to death. I will keep beating that dead horse until I make glue, and then I will use that glue to stick enough lights on a Christmas tree to illuminate my concept.

The point is, I’m going to use a metaphor a lot and contort it in various ways. But don’t worry. It’ll make more sense than that last paragraph.

Planting the Forest

During the creation of any game, creators make thousands of decisions that contribute to the whole, be it in narrative, game mechanics, character rigging, voice acting, and on and on. Every person on every team contributes bits and pieces that fuse together to form the player experience.

So, when I think about narrative design for games, I think a lot about the big picture. I want to be certain that the item names, dialogue, or plot choices that I make are engaging and follow the internal logic of the characters and story, but also that they align with the vision of the game’s world, suit the genre, and support larger narrative themes of the work. I call this “seeing the forest and the trees.“

Let’s lean into that metaphor a little: The smaller choices any creator makes are planting trees, spreading bark on the forest floor, frittering ferns about the place, and so on. The player’s experience of the game is a walk through the forest. They’ll see many of the small choices as they pick their path through the game, but they never see all of them. But if everyone has done their job, the player leaves with the experience of the forest.

A Wild Cactus Appears

At some point during the development of a game, a cactus erupts from the ground. A cactus can appear for any number of reasons, from practical to farcical, but the point is that someone or a team of people have created something that doesn’t fit.

It might be a subtle succulent that blends into the other foliage and hides in some nook of the game, or it might be a giant saguaro standing boldly in the player’s main path. Either way, if the player brushes up against it, it becomes a pain point in their experience that makes the player feel like something isn’t quite right. Sometimes the appearance of a single cactus causes players to throw down their controllers in disgust, while at other times players might roll their eyes at dozens of cactuses because they enjoy the experience of the walk through the forest. In whatever form the cactus appears, it affects consumer perception of the game and can depress sales.

The cactus could be a mini boss tougher than the end boss. It could be an anachronistic element in the scenery. It could be the voice of a character not fitting their body. It could be a character taking an unlikely action because of bad writing. Whatever the nature of the cactus, it arises because of a lack of communication and misalignment among the team.

Seeing the Same Forest

Take the idea inherent in my metaphor: Even if everyone agreed it was a forest, what’s to say it wasn’t a forest of cactuses? Even if we all agreed beforehand that it was a pine forest, if you’re not specific, it could be the cactus creator’s vision is of a desert forest where a cactus and pine tree might very well stand side by side.

If you’re the vision holder for the game, you have a responsibility to communicate that vision clearly, succinctly, and regularly. If you’re supporting the vision holder, you need to ask the right questions so that you can share their vision and develop the details your team needs to do its job. If you’re an individual contributor, you need to look up regularly from your assigned tasks to be sure you’re still doing work that aligns with the vision.

Different teams and individuals will need different levels of detail about any given concept around which they are expected to align. For some people, a vague understanding of the main pillars of the game and some buzz words are enough to get started, but even the most disconnected creator will eventually need more context.

Let’s return to our forest metaphor for a moment.

- Forest: A short PowerPoint presentation about the pillars of the mechanics, genre of the setting, and theme of the story.

- Pine Forest: A Word doc or PDF compiling comparable games with the unique ideas for mechanics along with an overview of this new game’s story and characters.

- Subarctic Coniferous Forest: All the above, plus supporting, more detailed documents with images of key characters and locations.

- Boreal Forest of the Alaskan Coast: All the above, plus full plans for the plot, player progression, and enticement and reward systems, detailed character backgrounds, the golden path, and so on.

It’s a lot. And you can’t do it all at once or do it all alone. Yet you must often get started even though you might only be able to align on part of the “Forest” stage. Regardless, you need to get closer to filling out a full vision for the game as quickly as you can, or before you know it, you’ll be surrounded by cactuses, coconut trees, kelp, and Venus flytraps with no clear way to smoosh all these creations into a cohesive whole.

But even with a full set of documents, it must be presented in a navigable form. People need to bite it off in chunks rather than being force fed by a firehose.

And there will still be gaps. You’ll discover a lot of places about which you need to learn more before you can create the right thing. But having a specific vision and proper documentation means that members of your team who go looking for answers to questions on their own will be more likely to find or develop the right answer.

Incommunicado

Often a gnarly cactus grows when an individual or a team works alone for too long. Even though they have all the tools they need to stay aligned with the vision, it can be easy to get into a creative grove, get excited by an idea, and not realize that their creation has gone off brief.

Dealing with these cactuses can be a prickly problem. Those involved didn’t see the problem while they were creating the cactus, and they aren’t likely to see it right away even when it’s pointed out. Even the most amiable creator who readily admits fault (a rare and precious gift to any team) might find their ego bruised or feel ashamed for having wasted time and resources. If you’re working under a lot of pressure, the appearance of a cactus might be considered a problem that could cost people their bonus or even their jobs. It’s understandable then that the cactus might have its defenders, both among the creators and the creators’ friends.

Whether you are the vision holder for the game or an individual contributor, pointing out the fact that someone else made a cactus can be dicey. That’s a big reason why I wrote this article. I hope to give teams some friendly language to discuss the sensitive issues when lines get crossed.

You can start early in the development process by asking “Is it a cactus?” about all kinds of elements. The answer will often be “no,” but sometimes it will be a little less clear. By examining the elements that make a concept wobbly, you can make choices that shore it up and—crucially—build those into your documentation about the vision of the game. Having regular conversations about aligning with the vision of the game will take some of the pressure off when a wild cactus truly erupts onto the scene. And remember, the reasons for creating a cactus are almost always innocent. And sometimes, they’re really good.

The Cool Cactus

After some early mistakes and adjustments, you now have a fantastic vision for the game and built up elaborate but accessible documentation to keep everyone updated and aligned with your mission. You know now that the Boreal forest doesn’t really reach the Alaskan coast, and you’ve adjusted your vision: The Cove of Spires in Kenai Fjords National Park near Seward, Alaska.

Perfect!

Then it struts into view to the beat of its own theme song, wearing dark shades and expensive shoes. It’s the coolest cactus you’ve ever seen. It’s wildly off brief, and the worst thing is that its creators knew it. They were inspired by something else cool they’d discovered in some other game or seen in a movie, and then they took the idea and improved it a thousand percent, creating something that feels fresh and looks magnificent.

Perfect…

- What do you do now? Well, you’ve got four options:

- 1. Adjust Your Vision

- 2. Alter the Cactus

- 3. Transplant the Cactus

- 4. Jam It In

Maybe you can figure out a way for the cactus to fit into your game. This is going to require multiple teams to make adjustments, and you might ruffle a lot of feathers. People who align closely with the vision laid out for your game will be particularly upset. The key to getting buy-in from such people might be counterintuitive: It might feel natural to praise the work of the cactus makers to convince them, but that could easily backfire. The people who have been doing their best to color in the lines won’t appreciate it when it seems like someone can just fingerpaint all over everyone else’s work so long as it’s “cool.” A better tact might be inviting them into the process of solving the problem created by the cactus while showing them the benefits of its inclusion. Their work might have been perfect as it was, and now they are forced to redo it, so consider teaming them up with the cactus makers to do the adjustments. This way, the cactus makers see the effects of going off brief and they help with the extra work they’ve caused. If the teams that must make changes see the cactus makers lending a hand, you might even end up with a stronger team dynamic.

Perhaps the cactus can be changed into something more appropriate (turning the cactus into a plant that might live in the forest). Or maybe there’s a way to fit the cactus into the environment by cordoning it off and highlighting its separate nature (putting it into a greenhouse someone built in the forest). This requires the help of other teams, but hopefully with less potential damage to the team dynamic and the overall vision for the game. However, this might come at the cost of some coolness of the cactus. Change it enough and you risk losing the very qualities that made it attractive enough to include in the first place.

You could simply set the cactus aside for later. This is the best course of action when you can honestly tell the cactus creators that their work is brilliant but too far off brief, and that they have the chance of including it in some other project. Indeed, you might find that at a later stage of the game’s development or for an expansion of game, it suddenly makes sense to put in that cool cactus. However, if there really is no place for their cool creation in the game, and you have no reason to believe it can be included in anything later, be honest. Sometimes people give the perfect answer to the wrong question, and you don’t get any credit for that.

What’s that you say? There’s a cactus standing on one of the spires in the Cove of Spires in Kenai Fjords? That is weird! But also, kinda cool, right? I mean look at it: It has sunglasses on and its own theme song!...

Okay, so the last solution really solves nothing. It betrays your vision of the game, ruffles the feathers of folks who adhere to the vision, and it might rub players the wrong way when they sense how out of place the cactus is in your pine forest. But in this case you’re betting that the cactus’s coolness overwhelms whatever reservations they might have about its inclusion.

If you jam it in, consider if there are other places in your game where you can plant cactuses. If they’re cool enough, cactuses can be the feature, not the bug. Your game becomes the awesome experience of something like the Alaskan Coast sprinkled with cactuses, creating some new alien environment. Turn into the skid, hit the accelerator, and see where it takes you. But realize that you might lose some folks along what is sure to be a bumpy road.

The Cactus Only You Can See

“It’s a green plant with needles. That’s exactly what you asked for!”

You’ve pointed out a cactus as diplomatically or as bluntly as you feel you must, but other people don’t understand what “your issue” is. Uh oh.

Either you’re misaligned with the vision, or they are. Either way, somewhere along the line communication broke down, and now you’re not seeing things the same way.

Conflict over creative choices can very quickly start to feel personal, so when you’re seeing a cactus and someone else isn’t, take a step back. Take a breather, go for a walk, listen to music, meditate, sit in your car and scream—do whatever it is that you need to do to view what you see as the problem with as much distance and detachment as you can muster. And then, set aside whatever rational arguments float to mind and instead try to open yourself to a different perspective. You don’t have to take the perspective of the other party. That might be too hard if you’ve already got firm convictions. Instead, imagine a third point of view. Look at the problem as if you are an alien come from space, or imagine what you’d think of it if you were someone from a different background, sexual orientation, or age.

When you’ve gotten the necessary distance from the problem, examine your assumptions. In what ways does it align and look more like a pine tree? Where might your understanding of the vision for the game and someone else’s have diverged? Is the issue a matter of emphasis, where perhaps you’re valuing aspects of the game’s vision differently? Is this an opportunity for both sides to learn something new about the game and have those discoveries expressed to the rest of the team?

It might make sense to take the issue before a team leader or a broader group to get the opinions of others, but you owe it to yourself to do that with an open and collaborative mindset. After all, you might be wrong, they might be wrong, you could both be wrong, the process might be at fault, or you might have received different marching orders for some reason. Perhaps they were out sick when there was an important meeting, or maybe you just missed a memo.

Succulent or Saguaro

Often the cactuses we see in games or movies exist because of the most banal reason: deadlines. It’s an inevitable fact that creative projects run out of time, and the timelines for digital games can be particularly punishing. There’s many a slip twixt the cup and the lip as everyone rushes to the finish line.

When you’re scrambling to make the release date, you need to spend your time solving the problems where your efforts will have the most impact on the player’s experience. A whole glade of saguaros presents a huge problem for your Alaskan forest, but if it is tucked away off the main trails, it might be less problematic than the succulents strung all along the golden path. On the other hand, there are succulents native to Alaska, and maybe the ones you have in your game are close enough that you really should figure out what to do about those saguaros. It’s all about how much impact your solutions will have on the player’s experience.

To make such decisions, you need to agree about the size of the problems you face. Is that cactus a succulent, a saguaro, or somewhere in between? If you’ve built up a strong shared understanding of the vision for your project, you should be aligned on what constitutes a problem, but by their very nature of being cactuses, they are outside the scope of your defined vision.

There might be a pithier way to describe this process, but here’s how I think about the steps:

- 1. Examine: Examine each cactus for how prickly a problem it presents to player perception.

- 2. Discuss: Discuss it with the team so that you all share similar standards for when other problems inevitably crop up.

- 3. Align: Align on the solution to the issue.

- 4. Assign: Assign the problem a priority based on size (succulent, stenocereus, or saguaro), and then assign the tasks of solving them based upon resources and impact.

What’s a Stenocereus?

It sounds like a dinosaur, but it’s medium-sized cactus, and it alliterates. So, in the spirit of beating the metaphor to death, it’s a way to categorize the medium-sized cactus that crops up in your game. Perhaps a prickly pear works better, or maybe you don’t need it. Either way, please give some thought to your cactuses and pine forests as you work on your game.

And with that advice imparted, let’s all bask in that twinkly light from the Christmas tree.

Canon Fodder

When someone starts talking about canon in relation to your game, you’ve made a mistake.

Why? Well, first allow me to digress a bit.

I love Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows. It’s a spectacular book well deserving of its place in the pantheon of great children’s literature. (Don’t get me started on how awesome the The Wind in the Willows TV series is.)

Anyway, at one point, my love for the book so overtook me that I scoured the internet to see if there was any more of it out there. And it turned out there was—although not by Kenneth Graham.

At this point, The Wind in the Willows is public domain (game developers, take note!), so other folk, who no doubt love the text as much as myself, endeavored to write sequels. What I discovered were William Horwood’s four novels that occur after the original and Jan Needle’s book that happens concurrently with the original story. (And there’s more!) While Horwood’s stories pick up the flag and admirably attempt to carry on, Needle’s work turns the original on its head by taking the point of view of the villains of the original story to comment on class barriers in Edwardian England (with a delightful result).

I read the stories, enjoyed them, and never thought once about whether the events of the books by the later writers “actually happened.” Yet if we turn this example around, and instead of talking about The Wind in the Willows we talk about Star Wars, Star Trek, or Game of Thrones, something else occurs.

This is because the sequels to The Wind in the Willows written by others are like slash fic written about Kirk and Spock. There is no expectation by the audience that the creator gave the go ahead for the later works. Nor does one owner own both the original and the later works.

What is Canon?

When used regarding fiction (or in this case, games) canon is simply the material for a property considered to be genuine. But such concerns only arise when users are given reason to question the validity of what is produced for the property. There aren’t canon concerns about CSI: Miami. The show has one outlet and is internally consistent.

In Star Wars, however, there are thousands of individuals that have contributed stories, characters, histories, locations, races and other details in media as diverse as toys, comics, novels, movies, and TV shows. When you have that many contributors working concurrently to produce material in so many different places, it’s impossible for anyone to keep track of it all and be a gatekeeper both for inconsistencies and for bad material. (Did you know there was a green-furred rabbit race in Star Wars?)

Canon concerns happen when two ingredients interact:

- an authority over what is true for a property

- an inconsistency under that authority’s rule

As consumers of setting and story, we naturally assume that the elements within that setting or story should remain consistent unless there’s some in-world reason for a change. If we’re told a character is an orphan, that character’s parents can’t suddenly appear without an explanation as to why we were earlier told the character had none.

Why is Canon Bad?

When people start talking about what is canon in your property, it means that there’s confusion about it. Somewhere along the way something done for your property has turned some element of it into a lie. Not only does it make you look bad, it can be divisive, splitting fans into factions and causing endless internet arguments.

Ultimately, canon issues give your audience the impression that you don’t take your property as seriously as they do. While any property can withstand that for a while, it’s one of the factors that causes consumers to lose confidence in your brand.

Why Does Canon Happen?

While any mistake can cause a canon problem, it’s likely that you will create canon issues when any of the following factors occur with your property.

- Continuing Story: If your property has a story that continues (in sequels, novels, or episodes of a series) you’re in the danger zone. Keep a close eye on the details.

- Long History: If your game features a lot of fictional history, you’re canon fodder! Fictional histories create a minefield for creators. They’re details that are largely out of sight but surprisingly present in the “present” of your game. One false move and whammo!

- Broad or Deep Setting: If your game has a lot of details about the present setting, that becomes almost as bad as a deep fictional history. Having detailed descriptions of the current events or politics in many nations or having a lot of material written about the inhabitants of a single town puts any creator for your game in the unenviable position of reading all that material and not forgetting or confusing any of it.

- Multiple Contributors: When you have multiple creators, they will not use an identical standard for content nor will they all be perfect at keeping in mind history, setting, or any other guidance they might have. You can try to stay on top of this by limiting the number of creators to where it’s manageable for one person read all their work and smooth out differences, but that person will at some point miss something.

- Multiple Media: Changing the medium often demands altering the message. Plus, putting out content both through a game and another medium means that anyone who is trying to keep things straight must manage the transitions from one medium to the next. Pity the writer of a 16-page comic book who has to read a trilogy of 300-page novels in order to present things correctly.

- Concurrent Design: If you’re working on several products for your game at the same time, that’s a huge red flag. It’s far too easy for the left hand not to know what the right hand is doing (or the other left hand, or the other right hand, or the leg, or the other leg, or . . .).

- Changing Standards: Your game property might change owners. It might get new staff as old staff leave. You might have a new product goal that demands you look at your property in a new way. Perhaps your gatekeepers grow lax or more stringent about one thing than another. Whatever it is that causes you to change your standards for how fiction for your game is produced, your fiction’s fans won’t have gotten the memo, and even deliberate changes for the good of your property will look like mistakes to them.